On-Set Production – Critique of Final Work

On-Set ProductionOne More Day – Final Film Link

Critique of Final Work – Analysis + Interpretation

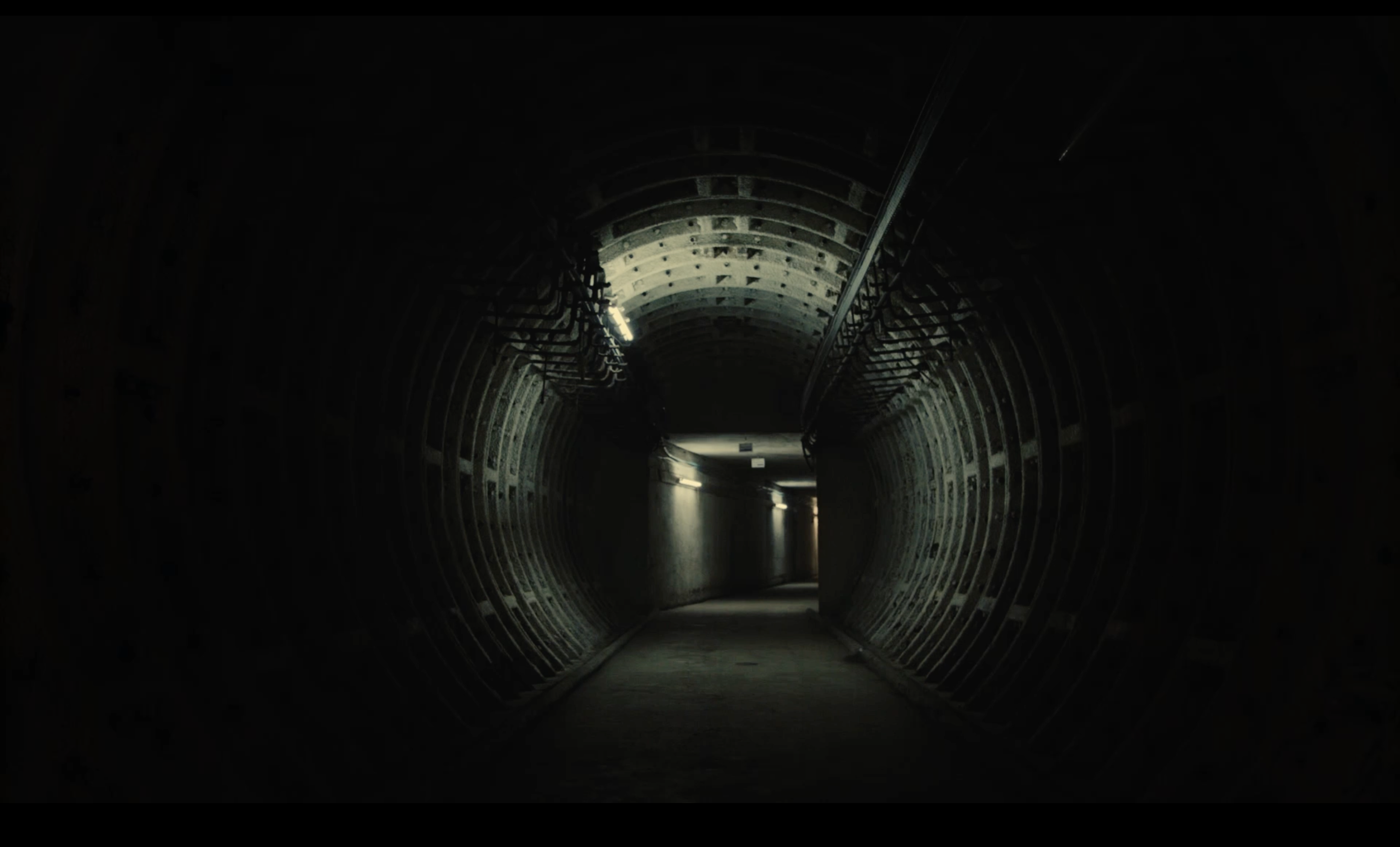

The first two shots of ‘One More Day’ make it apparent this is a post-apocalyptic film. The flickering light in the tunnel and dilapidated hallway are visual motifs of the genre. The opening shots create a sense of isolation and loneliness by showcasing these empty spaces devoid of life. They establish we are underground and in a place where people did not go by choice.

We move to a closeup of a tin of dog food eaten with lacklustre. This reinforces our initial suspicions about the post-apocalypse nature of the film. We are not concerned with who is in the bunker, but the conditions that they live in.

We first see our characters, Cam and John, from an unusually high angle, mimicking the height and positioning of a CCTV or surveillance camera, echoing their shared paranoia. This indicates nothing about their dynamic but showcases the established base they co-habitat. It appears they have been here for a long time.

Cam, the protagonist, is lit with almost a spotlight effect from the overhead and practical lights, signalling a sense of importance.

The previous shot of Cam features warm lighting and contrasts with the shot of John. John sits further into the shadows, lit from the back and side, silhouetting him against the space. The colour temperature subtly hints at the emotional and mental state of each character: Cam, who presents as more animated and optimistic in parallel to John, who is docile and disparaged.

John is purposely viewed from a high angle throughout the film, implying a sense of inferiority and meekness.

The dialogue tells us that there is an underlying grief and tension, affirmed when John recalls mac and cheese was Sarah’s favourite. We cut away to children’s drawings, confirming the suspicion that someone else used to live with the two and they were close.

Cam seems frustrated with John and his refusal to fix the radio, symbolic of his abandonment of the hope and will to survive. This becomes apparent in the shot of Cam almost threateningly looming over John as he attempts to convince him to fix the radio.

The radio symbolises a more significant issue between the two, as John halfheartedly fidgets with the dials.

Cam recedes into the darkness as he imagines life without John, creating anticipation and foreshadowing. Cam is no longer in the spotlight, and his intentions seem less obvious.

Cam and John swap to opposite sides of the room. We see John clearly for the first time as he sits down to eat and looks at the drawing Sarah made for Cam. Out of focus in the background, Cam examines the radio, picks it up, and walks towards John. He swings the radio at his head, but the impact is heard off-screen.

The blood splatters across the drawing, creating a sense of intrigue about what happened to Sarah and how Cam’s frustration with John’s hopelessness has resulted in his murder. The shot is purposely dark, with highlights of the blood reflecting the little light there is.

We see Cam from an extreme high angle, with the radio appearing as large and prominent in the foreground as Cam himself. The blood can be seen on the corner. The radio is a character in the film. It begins to pick up a signal through the static, creating dramatic irony and solidifying the dark, unforgiving nature of One More Day.

We revisit the same shot of the tunnel in the bunker, and the lights slowly flicker out, representing either the death of John or the isolation Cam now faces. The tunnel and the radio serve as visual motifs for One More Day, each serving a dichotomy of hope and despair.

Critique + Independent Audience Review

One More Day is a morally ambiguous film as we are given minimal backstory to Cam and John and have few references to the other people who used to occupy the bunker, like Sarah. Using blocking and camera angles to illustrate Cam and John’s characteristics and power dynamic, we can infer that they have reached a breaking point in their relationship that must be resolved.

One More Day features low-key lighting to draw attention to body language through backlighting and silhouetting, creating a sense of mystery around John’s character. By contrast, Cam is evenly lit in the film’s first act as his intentions are clear and less conflicted – he wants John to fix the radio and prove he still has a survival instinct and hasn’t given up. Cam moves into the shadows when he realises John has become a liability and swaps to place John in the foreground of the shot as he lurks in the background, plotting his next move.

The film’s success lies in what is implied and not explicitly stated about the story. We are positioned to interact with Cam and John first as an observer through the surveillance-like wide shot and then as active participants in the narrative when we are brought down to their level. We see Cam and John as they see each other, moving from light to darkness and strength to weakness.

I wish we had planned close-ups to convey the depth and subtlety of emotion in Cam and John, particularly at the beat/shift in the middle of the film where Cam realises he needs to put John out of his misery, as without the closeup, the moment is lost. Close-ups would have also highlighted the claustrophobia of the situation. I am not sure that the angle and height of our wide shot conveyed what we intended – a sense of claustrophobia and surveillance – and that we generally relied upon wider shots too much throughout the film, given it is character-led.

Overall, I believe that the cinematography for One More Day conveys what the script and other elements of the mise-en-scene do not about Cam and John and their relationship. The visual language of One More Day is clear and well-established, so when it is subverted later in the film, we suspect a change to their dynamic or the narrative outcome.